Not Your Father’s Privacy – Take 2

Thanks to Edward Snowden, we now know with much more detail how much information about us – every one of us – is being gathered and analyzed by our government. In the end, Snowden may wish he had chosen to reveal his identity from a country that does not have an extradition treaty with the U.S., but that’s his problem.

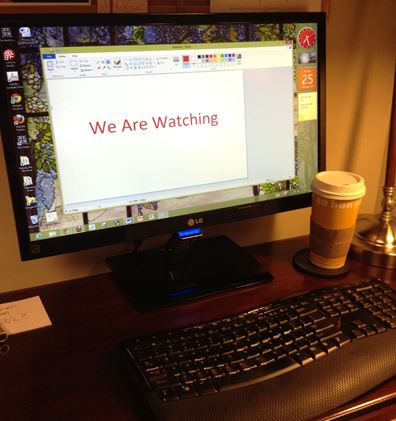

I say we know more than we knew, because any one of us who logs on to Google and is presented with ads for products suspiciously like those we tend to want should have known that someone, somewhere, was “watching” our online behavior. In February, I was out in Silicon Valley visiting the offices of Modria, a start-up ODR company with which I am involved, and I had the chance to hear one part of the “State of the Valley” conference and talk to a couple of people about the kind of market research and data analysis that is being done in the commercial world. On February 25, I posted a blog note about the conference, including this aside.

Coincidentally, last week Alan Westin died. Westin was the Columbia professor of public law who wrote the seminal text in privacy law (Privacy and Freedom), extending Brandeis and Warren’s argument that privacy is a right – the “right to be left alone.” Westin’s original position was that individuals have a right to control what information about them is distributed, to whom, and in what circumstances. That idea seems quaint now . . . . In the end, Westin’s attitude seemed to be that we can no longer control the information about ourselves that is public, and that privacy law should shift focus to protect our right to make sure that the information circulating about us is at least accurate. I’m not sure there is any deeper meaning in the juxtaposition of these two events than simply being another marker in the physical passing from the age of digital immigrants to the age of digital natives, but it does highlight that among all the other changes that the use of online communication tools has brought about, what we have now is ‘not your father’s privacy.’

Not your father’s privacy, indeed. The data analysis techniques being used, and to some degree perfected, in the commercial world have, at least since 9/11 been used to analyze the communication patterns of potential terrorists, which is to say the communication patterns of everyone who uses telephones, mobile phones, or the Internet. This should surprise none of us. Intelligence organizations have a history of using the best available sources to gather information that goes back at least to the Bible. Having a concubine report on the goings on in the palace may be an appealing way to get information, but data mining phone and Internet use is obviously a lot more effective in the long run.

Any terrorist worth his or her salt already knew that near universal surveillance exists. It is no longer paranoid to assume that, at any given moment – as I load this onto my blog, for example – some organization, or several organizations, are recording what I’m doing, or taking photos from hidden cameras, or looking down from drones too high for me to see but with cameras that can pick up the image of the quarter I dropped on the sidewalk. In one sense, what Snowdon revealed is no more than what the reasonably paranoid among us already assumed. But in another sense his leak can be seen as damaging to both the intelligence community and the rest of us. The intelligence community is no longer hiding behind a curtain of secrecy to the extent that they were before Snowden’s leak, so they now have to defend themselves and are to some degree damaged. But the rest of us may suffer, too. Whatever one thinks of the fact of the data gathering, before Snowden’s leak all of us, including the terrorists, had to guess at the extent and nature of the data being gathered. Now, some of that information is public. As an acquaintance of mine who was an old-school spy once told me, anything at all that your enemy finds out about you, no matter how trivial it may seem, adds to the store of data about you, and helps them predict your behavior or understand you better. Snowden’s leak certainly gives our enemies some information they did not have, and that is potentially dangerous for us all, and may be the reason that his choice of Hong Kong as a place to “come out” wasn’t all that smart. The intelligence community is bound to be a little irked with him.

The vigorous debate over whether Snowdon has committed an act of treason or an act of patriotism is already well underway. I think it is possible to think of his actions as both treasonable and patriotic, but in our currently polarized society that’s not likely to be a majority opinion.

What is clear is that, no matter which side of the argument one is on regarding Snowdon’s leak, you can just pick your cliché to describe the current state of privacy in the United States: that horse is out of the barn, that ship has sailed, etc., etc. President Obama says emphatically that the government is not “listening to your phone calls” – that may or may not be true at the moment, but what is undeniable is that the advances in natural language research and data mining that are happening both in the private sector and the public sector mean that the government could listen if it wanted to. And why, in a world where we define a sizeable portion of humanity as potential enemies, would the government not want to listen?

The most troubling, and either dishonest or stupid, argument that I’ve heard from the intelligence community is that the data being collected is “just sitting there,” stored for use only if there is reasonable cause to mine it. That may be technically true at the moment, but anyone who has ever dealt with organizations knows that things that are not supposed to be made public somehow become public, and things that are supposed to be unused or benign find their way into nefarious uses. To say that the data being collected cannot be misused is at best naïve and at worst dishonest.

Imagine a case in which, years from now, a candidate is running for President of the United States. In fact, if you are in your 20’s or 30’s now, imagine yourself in that position, as a candidate, 30 years from now. How comfortable would you be knowing that somewhere, in a data base that is easily searchable and analyzable, is information about every phone call you made, everyone with whom you communicated, and every Internet site you visited from the time you were in your 20’s?

It really isn’t your father’s privacy.